Were There REALLY Bloody Video Games in the 1980s?

In the early ’90s, Mortal Kombat and NHL Hockey became lightning rods for controversy. With their bloody finishers and brutal gameplay, they alarmed parents and lawmakers, prompting Congressional hearings and the creation of the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) in 1994. But the roots of violent and adult-themed gaming stretch back much further—to the early 1980s, when a small publisher called Wizard Video Games tried something no one else had.

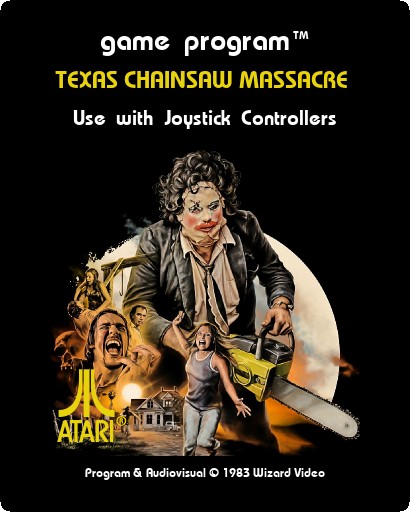

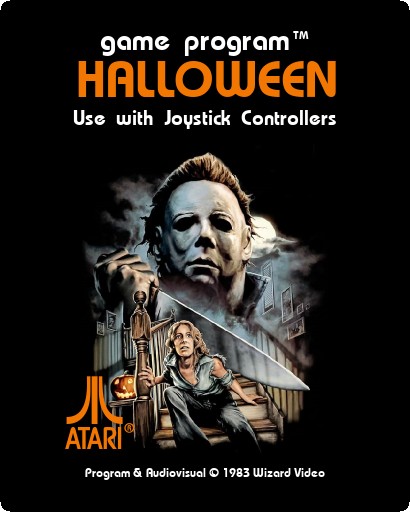

An offshoot of Charles Band’s Wizard Video—known for distributing grindhouse horror on VHS—Wizard Video Games released two infamous titles for the Atari 2600: Halloween and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. They weren’t just early horror games—they were among the first to bring graphic violence and mature themes to home consoles, pushing the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in gaming at the time.

Wizard Video Games

Founded around 1982, Wizard Video Games was created to adapt slasher films into interactive experiences. The idea was bold: let players relive iconic horror movies on the Atari 2600. But these weren’t just spooky—they were shockingly graphic for the era.

In Halloween (1983), players assumed the role of a babysitter trying to save children from Michael Myers. If caught, she was decapitated in a burst of pixelated blood. In The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1983), players actually controlled Leatherface, chain sawing victims for points. Both games were panned for their content, and major retailers refused to stock them. Wizard Video Games folded soon after.

Despite their failure in the marketplace, the games have since earned cult status, not just for their rarity, but for how far ahead of their time they were.

Horror, Porn, and Public Morality in 1983

To understand the reaction to these games, it’s important to look at the broader media landscape of the early ’80s. This was a moment of transition—and tension.

The horror genre exploded in the ’70s and early ’80s, with slasher films like Halloween and Friday the 13th dominating theaters. Meanwhile, the adult film industry was shifting from theaters to home video, thanks to VHS. This accessibility sparked a boom in X-rated content—but also drew backlash.

Religious groups and the Reagan administration ramped up efforts to crack down on “obscenity,” and feminist critics increasingly called out the portrayal of women in porn and horror alike.

Video games weren’t immune. As developers flirted with mature themes, watchdog groups started paying attention.

The First Game Controversy: Death Race (1976)

Long before Mortal Kombat, there was Death Race. Released in 1976 by Exidy, the arcade game had players run over “gremlins” that many interpreted as human stick figures. Each kill left behind a gravestone and triggered a scream.

The game caused a national stir. Media outlets like 60 Minutes and The National Enquirer ran sensational stories. Public backlash led some arcades to remove the machines—but the controversy only increased its popularity.

Death Race was arguably the first violent video game scandal, setting the stage for the moral panics to come.

Adult Atari Games

Around the same time Wizard was experimenting with horror, another group of developers was combining gaming and pornography.

Mystique, active from 1982 to 1983, released X-rated titles for the Atari 2600. Its most infamous game, Custer’s Revenge, featured General Custer dodging arrows to assault a naked Native American woman. It drew immediate fire for racism and sexual violence.

Other Mystique titles included:

- Beat ‘Em & Eat ‘Em – where players caught falling bodily fluids and

- Bachelor Party – a sexual spin on Breakout.

These games were widely condemned for being tasteless and poorly made. Mystique quickly folded, and their catalog was bought by Playaround, which re-released the games—sometimes with “gender-swapped” versions, including General’s Retreat, an opposite version of Custer’s Revenge.

While they were barely games in the traditional sense, they helped draw a line in the sand about what was acceptable—and paved the way for the ESRB system years later.

Wizard’s Legacy

While Mystique went for shock, Wizard Video Games tapped into something more enduring: fear.

In Halloween, the player’s only goal was survival. You couldn’t kill Michael Myers—only run, rescue children, and temporarily stun him with a knife. The chiptune version of the Halloween theme played whenever he appeared, creating real tension. For its time, the atmosphere was groundbreaking.

Texas Chainsaw Massacre offered something different: you played as the villain. This role reversal would inspire later games like Manhunt and Dead by Daylight. Players had to manage fuel for the chainsaw and avoid obstacles like wheelchairs and fences. Run out of fuel, and it was game over.

Both games were primitive by modern standards, and critics slammed their repetitive gameplay. But they laid the foundation for key horror gaming mechanics: vulnerability, pursuit, and dread.

How These Games Were Sold

Since retailers refused to stock games like Halloween, Chainsaw Massacre, and Mystique’s titles, distribution happened through unusual channels:

- Adult bookstores and video shops, often in back rooms.

- Mail-order catalogs in magazines like Hustler and Penthouse.

- Independent electronics stores, selling under the counter.

- Conventions and trade shows where content restrictions were looser.

This niche distribution made the games hard to find even in their own time—one reason they’re so valuable today.

The Flesh Gordon Mystery

Charles Band, the man behind Wizard Video, would go on to greater fame in the home video market. He founded Full Moon Features in 1989, releasing cult hits like Puppet Master, Trancers, and Demonic Toys. His films were fast, cheap, and wildly imaginative—tailor-made for the VHS generation.

Before leaving gaming behind, Band had one last project in mind: an Atari game based on Flesh Gordon, the 1974 sci-fi sex spoof of Flash Gordon. Campy, raunchy, and filled with stop-motion monsters, the film was more playful than explicit.

For decades, it was thought the game never existed. But years later, a programmer confirmed it had been completed: “It sucked—sometimes literally,” he said. “The ‘reward’ was humping with the joystick. It was terrible.” No ROMs have surfaced publicly, but rumors persist that one may be in a private collection.

What They’re Worth Today

Due to their rarity and infamy, Halloween and Texas Chainsaw Massacre are among the most valuable Atari 2600 games ever made.

- Loose cartridges sell for $300–$800 (Halloween) and $200–$600 (Chainsaw).

- Complete-in-box (CIB) versions go for $1,500–$5,000.

- Factory-sealed copies, if found, could be worth over $10,000.

Their limited release, retailer rejection, and shocking content make them prized among collectors.

Lasting Impact

Despite their flaws, Wizard Video Games introduced important elements that shaped the horror gaming genre:

- Survival gameplay where the player is defenseless (Halloween).

- Playing as the villain, years before it became common (Texas Chainsaw).

- Film-to-game adaptations, a trend now common in horror titles.

Games like Resident Evil, Clock Tower, and Outlast owe some of their DNA to Wizard’s early experiments. So do modern film tie-ins like Friday the 13th: The Game and Evil Dead: The Game.

Conclusion

Wizard Video Games only released two titles, but their influence is far-reaching. They challenged norms, tested boundaries, and—intentionally or not—helped define the horror gaming genre. At a time when gaming was seen as wholesome family fun, Wizard dared to bring blood, fear, and even adult humor into the mix.

Today, Halloween and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre are remembered not just for their shock value, but for their role in gaming history. They helped prove that video games could be more than toys; they could be provocative, controversial, and even scary.